Ongoing protests in Colombia are of a scale not seen since the assassination of Jorge Eliécer Gaitán in 1948. Though they began as a response to specific economic and social reforms, the national strike led by a broad yet diverse coalition of movements and organisations has become a lightning rod for longer-term discontent about the failing peace process, the killing of hundreds of social leaders, unequal access to education and health services, and a low-wage, extractive, neoliberal economic model. Like other parts of Latin America and the wider world, Colombia is finally waking up, write Tobias Franz (SOAS) and Andrei Gómez Suárez (University of Bristol).

Ongoing protests in Colombia are of a scale not seen since the assassination of Jorge Eliécer Gaitán in 1948. Though they began as a response to specific economic and social reforms, the national strike led by a broad yet diverse coalition of movements and organisations has become a lightning rod for longer-term discontent about the failing peace process, the killing of hundreds of social leaders, unequal access to education and health services, and a low-wage, extractive, neoliberal economic model. Like other parts of Latin America and the wider world, Colombia is finally waking up, write Tobias Franz (SOAS) and Andrei Gómez Suárez (University of Bristol).

• Disponible también en español

South America is once again on the cusp of changes that will fundamentally shape the political, social, and economic future of the continent. While Latin America more broadly has tended to be seen as a laboratory for neoliberal policies, the region has also been the setting for massive popular mobilisations against political repression, state violence, unemployment, inequality, and corruption. Colombia, however, has been something of an exception. Until now.

Protest in Colombia, from Gaitán to Duque

The last major mobilisation occurred in 1977 when Colombians took to the streets to protest against the López Michelsen presidency. But today’s protests, kickstarted by a nationwide general strike on 21 November 2019, are the largest since the 1948 “Bogotazo” riots that followed the assassination of the popular leader Jorge Eliécer Gaitán.

Though the stability of the political realm was severely tested throughout half a century of (mostly) rural guerrilla warfare, the same oligarchic elites that have held considerable power since colonial times managed to keep Colombia’s polity relatively stable. The absence of successful popular uprisings kept organisational power highly concentrated.

Unusually, however, the recent national strike has attracted support from all across civil society and throughout the entire country, leaving Colombia on the brink of historical changes that will shape its destiny for generations to come.

Against the backdrop of the historic 2016 peace agreement between the Colombian government and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), the recent national strike has brought together trade unions, peasant and indigenous groups, Afro-Colombian councils, and the women’s and student movements. Though it was planned well in advance, giving the right-wing president Iván Duque (2018-) ample time to prepare, even after three weeks of protest the government has been unable to undermine Colombians’ determination to change the society in which they live.

The original strike was a response to Duque’s proposed package of economic and social reforms, which would benefit big business while further disenfranchising the working classes, indigenous groups, young people, women and ethnic minorities. But frustration with the government runs much deeper.

A structural lack of support for public education, the myriad failings of a privatised health system, a continuous crackdown on democratic rights, the targeted killing of hundreds of social and indigenous leaders, and the sabotaging of the peace deal provide the slower-burning fuel that has driven the national strike forward.

The role of civil society and social movements

The current protests did not emerge from nowhere, however. Even during the latter stages of negotiations between Santos government (2010-2018) and the FARC, various sectors of civil society formed so-called “pro-peace networks”. These networks have since mobilised to defend the peace deal, to ensure implementation of its many stipulations, and now to call for street demonstrations. The national strike has provided a platform for strengthening these networks, creating synergies between actors and allowing them to synchronise agendas and operational approaches.

Human rights organisations have called for participation in the strike as a means of rejecting the killings of social leaders, disproportionate use of force by the armed forces, and the return of extra-judicial killings. Environmental activists, meanwhile, carried out a “Strike for the Planet” to oppose the government’s decision to authorise fracking in the vital Andean tundra (páramo) ecosystems and shark fishing in Colombia’s territorial waters. The protests on 25 November were led by women’s organisations in a concerted effort to raise awareness about the International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women.

Flashmobs, concerts, street theatre shows, and countless other artistic performances have been taking place throughout Colombia ever since. The creativity shown by the multitude of movements coming together via the national strike is a reflection of how quickly pro-peace networks have come to recognise their own power, not only on social media but more importantly in streets and plazas all over the country.

Responses to the national strike

These continuous, multi-faceted demonstrations have forced the Duque administration to call for a “national dialogue”. But the exclusion of the national strike’s organising committee from the first day of that dialogue soon revealed this to be a hollow promise.

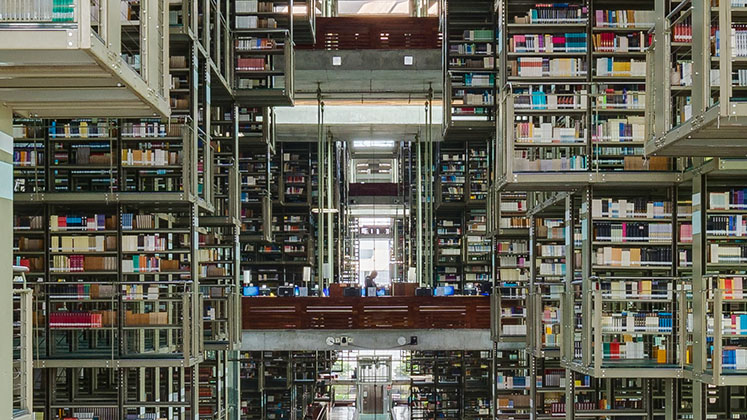

On 3 December, an attempt at dialogue between Duque and the organising committee came to nothing because one of the committee’s key demands remained unmet: to stop calling out the notoriously violent riot squad of the National Police (ESMAD, pictured above), whose agents were responsible for the killing of 18-year old Dilan Cruz during protests in Bogotá.

On 4 and 8 December 2019, Colombians took to the streets yet again, and new demonstrations are planned before the end of the year and well into 2020. Full implementation of the 578 stipulations of the peace deal remains one the most heartfelt demands. Pro-peace networks want to see commitment and determination from the government in its peacebuilding efforts.

Wider Colombian society was slow in recognising the reduction of violence that came with the peace process, but daily reports in traditional and social media about a return to war stir memories of the worst years of armed conflict, and Colombians across the country are standing up against the government.

The national strike and Colombia’s economic model

Aside from fighting for proper achievement of the peace deal, protesters are also resisting the economic regime implemented in Colombia since the 1990s. As with uprisings in Beirut, Hong-Kong, Santiago, and Quito, the recent mobilisations have been a response to a neoliberal turn that increased inequality, sacrificed public education to private profit, disenfranchised women, marginalised indigenous and Afro-Colombians, destroyed endemic flora and fauna, promoted deforestation of the Colombian Amazon, and intensified political repression. Today’s protesters want to move away from a model based on the extraction of natural resources and the exploitation of cheap labour in low-productivity services and labour-intensive agro-industries.

The government, however, has responded by promising to reinforce Colombia’s neoliberal economic model. Rather than addressing protesters’ concerns, President Duque used a speech on 25 November to defend private property, to double down on his commitment to economic reforms, and to defend violence against protesters by security forces. While the precise details of this reform package remain unknown, leaks have revealed that his government plans to eliminate (and privatise) the state-run pension fund Colpensiones, reduce the salaries of young people to 75 per cent of the minimum wage, lower taxes for large companies, and raise energy tariffs by up to 35 per cent. Duque even had the audacity to sign a decree creating a holding company for 19 state financial institutions while protests were still ongoing, which only served to reinforce existing opposition to privatisation and deregulation.

A core concern for protesters is growing inequality in access to high-quality education. Students from both public and private universities have already mobilised several times in 2019, and they have been at the forefront of the national strike’s demand for an end to austerity measures. They call for more investment in education and the fulfilment of a $1.3 billion investment promised last year by the government after more than two months of protests. Minister of Education María Victoria Angulo has reaffirmed that the government is allocating resources to education “like never before”, but public universities remain underfunded just as state-sponsored programmes that favour private higher education continue to expand.

The word neoliberalism is roundly used and abused these days, but here it is appropriate: preservation of an imbalance of power that reinforces extremely unequal distributions of wealth, accompanied by violent repression of subaltern classes, is an inherent feature of this ideology. The ongoing uprising of the working and middle classes in Colombia should thus be seen as resistance to the deepening of the country’s neoliberal development strategy.

Is Colombia waking up?

In the Colombian context, where oligarchic elites have ruled the country with a dogged determination to maintain a balance of power that favours them, strategies of capital accumulation have always been accompanied by high levels of violence and oppression. During recent strikes, pro-peace and anti-neoliberal networks have come together to bring about change. Though this is a long and arduous process, the strength of the protests lies in its ability to mobilise across the whole spectrum of civil society.

Between workers demanding better labour conditions, women’s movements rejecting patriarchal structures of violent oppression, students standing up for their right to education, indigenous groups and Afro-Colombians fighting the colonisation of their land and bodies, social leaders pressing for fulfilment of the peace deal, the movement that has taken the streets of Colombia is here to stay. And the tide seems to be turning.

After centuries of exclusion from political and economic life, the Colombian people are fighting back. Colombia is waking up.

Notes:

• The views expressed here are of the authors rather than the Centre or the LSE

• Please read our Comments Policy before commenting