Women walk past citadel, Erbil, Iraq, 2011. Flickr/Adam Jones. Some rights reserved.Oil, independence, the radical Islamist threat, internal political strife, and economic challenges are the themes that dominate discussions about the Kurdistan Region of Iraq (Iraqi Kurdistan). Women as a topic of discussion rarely come up, despite the existence of vibrant local activism around women’s rights and international acknowledgement that the inclusion of women in post-conflict reconstruction can lead to more durable, peaceful and inclusive societies.

Iraqi Kurdistan is an autonomous region of Iraq. The region gained de facto autonomy in 1991 after the US intervention under George Bush Sr. and the creation of a ‘safe haven’ to protect the Kurds from attacks by Saddam Hussein’s regime in Baghdad. Iraqi Kurdistan’s autonomous status was later officially recognised after George W. Bush’s intervention in 2003. This created a powerful decentralised local government, the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG), which since its formation has consistently expressed its desire to comply with international standards in the rule of law and governance. Enhancing women’s status has been one of the key aspects of this goal.

It was against this backdrop that, in 2014, the KRG and the Iraqi government jointly launched a National Action Plan that sought to implement the UN Security Council Resolution 1325 on Women, Peace and Security. This is the most recent document that displays to what extent domestic laws and policies follow the international standards on women’s rights, although it is not the only one. Some years earlier the Declaration on the Elimination of Violence against Women was passed by the Iraqi parliament and was also binding over Kurdistan.

One thing is certain – women in Iraqi Kurdistan are better off compared to their counterparts in the rest of Iraq. Iraqi Kurdistan fares better when it comes to women’s participation in decision-making and when it comes to laws against gender discrimination. But are women in Iraqi Kurdistan also better off compared to women in other states in the Middle East and in the world? No. Kurdish women still face serious challenges, such as patriarchal attitudes towards women’s participation in social, political and economic life, honour killing, gender-based violence, and female genital mutilation.

Challenges women face in Iraq Kurdistan

Although Iraqi Kurdish law treats honour killing as just like any other murder, the practice continues and local women’s organisations believe it is increasing. Kurdish government’s statistics for 2013 reveal that 236 women suffered injuries from having been burned as honour punishments, and another 113 from self-immolation. The forensic institute in Iraqi Kurdistan reported the deaths of 1,748 women by burning, shooting or suffocation in 2013. According to a UNICEF survey, 43% of women aged 15-49 in Iraqi Kurdistan reported they had been subjected to some form of female genital mutilation (FGM) in 2011. WADI (Association for Crisis Assistance and Solidary Development Cooperation) found that the rate of FGM in the Sulaymaniya and Erbil governorates of Iraqi Kurdistan was above 70% in 2010.

The implementation of new laws and policies is another area where women remain vulnerable in Iraqi Kurdistan. This is true in part because the reference to sharia law in the Iraqi Constitution is very vague. This leads to different interpretations of Islamic rules, which makes unitary legislation difficult and leaves spaces open for patriarchal interpretations. Men and male judges govern most courts and often do not implement new gender-sensitive laws. The first female judge in Iraqi Kurdistan, Nigar A. Muhammed, stated that out of 250 judges in Iraqi Kurdistan, only 12 of them were female in 2014.

Even when women are better represented in governing institutions, this does not always lead to significant gains. Despite women’s presence in the parliament and in local councils, the number of women occupying executive positions remains very small. Among the 21 ministries in the current Kurdish government there is only one female minister (municipalities and tourism). Most female representatives rely on securing the nomination of male party leaders for their positions. This means they are forced to act in accordance with their party’s attitude on women’s issues and do not or cannot initiate more profound change.

In short, women’s participation in political and economic life remains limited. According to Kurdish local organisations and activists, this is due to a range of factors including a lack of awareness when it comes to women’s rights, the fact that women are economically dependent on men, the heavier burden on women for childcare and family responsibilities, and the influence of conservative views of religious and tribal authorities on the role of women in society. Government officials defend their poor record on women’s rights by stating that priority has to be given to security and stability, and that economic development and women’s issues are secondary in importance at the moment. They argue that the KRG has only limited economic and institutional capacity to implement and monitor new laws and regulations to improve the position of women.

Women in Iraqi Kurdistan are better off than women in the rest of Iraq

Kurdish women enjoy more participation in politics and socio-economic life, more gender-equal laws, and better opportunities for civil society activism than other women in Iraq. Women in Iraqi Kurdistan are also relatively less negatively affected by issues caused by conflict and security, such as violence inflicted by militias, targeted abuse, rape, abduction, and the vulnerabilities brought by displacement.

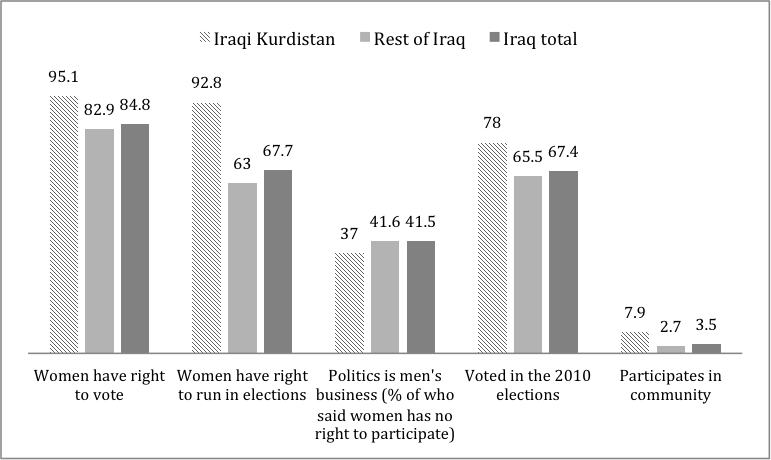

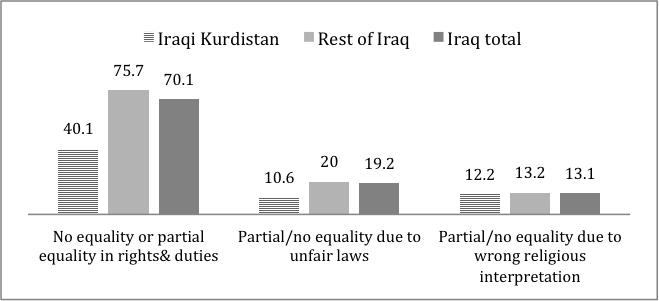

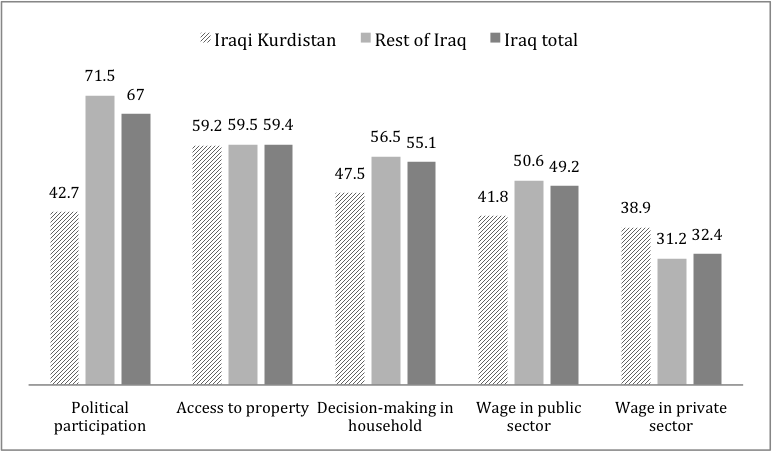

The Iraqi Women Integrated Social and Health Survey (I-WISH), released by the Central Statistical Organisation at the Ministry of Planning in Iraq in 2012, reveal that Kurdish women aged 15-54 have a relatively positive perception on their political participation rights, gender equality, and balance in society compared to their counterparts in the rest of Iraq (Figures 1, 2 and 3). Having said that, the survey also shows that many issues remain, including those related to women’s participation in public life, educational attainment, gender roles, and gender-based discrimination and violence.

Figure 1: Women’s (aged 15-54) view on participation in politics (%). Source: Central Statistical Organisation, Iraqi Women Integrated Social and Health Survey (I-WISH) (Baghdad: Ministry of Planning, 2012).

The UN’s Gender Inequality Index also shows that Iraqi Kurdistan is relatively better off than the rest of Iraq. This measures gender inequality based on reproductive health, empowerment and labour market participation. It ranges from zero to one, where the lower the score the more equality there is between women and men. Iraqi Kurdistan achieves a score of 0.41 compared to the rest of Iraq at 0.55. According to the same data, Kuwait, Turkey and Saudi Arabia have indices of 0.27, 0.36 and 0.68 respectively.

Iraqi Kurdistan applies a higher gender quota than Iraq for women’s participation in decision-making in the parliament, legislative, provincial and governorate councils. The quota is 30% in Iraqi Kurdistan while it is 25% in the rest of Iraq. The KRG has also amended Iraqi law and passed additional laws in ways that increase gender equality in the region. Restrictions were introduced to the law on polygamy to limit a husband’s ability to have multiple wives. The law relating to honour killing was amended to remove the reference to mitigating circumstances that alleviate the punishment of perpetrators. The Law Against Domestic Violence, adopted in 2011, holds perpetrators more accountable for their actions, including acts committed by husbands against their wives, and offers more protection for the victims. The government also introduced a new law in 2011 to ban the FGM.

Figure 2: Women’s (aged 15-54) perceptions on gender equality in society (%). Source: I-WISH, 2012

The Kurdish government established new bodies to deal specifically with women’s issues. A special directory to follow up on cases of violence against women was established. Special domestic violence courts were instituted in all three Kurdish governorates. The High Council of Women’s Affairs was established to advise the government on gender-mainstreaming policies and developing appropriate strategies.

Civil society organisations working on women’s issues flourished in the region, receiving support from the UN, international NGOs, foreign states and the Kurdish government. They were also more able to carry out activities compared to their counterparts in the rest of Iraq due to greater relative security and stability in Iraqi Kurdistan.

Figure 3: % of women (aged 15-54) reported gender balance is favourable to men. Source: I-WISH, 2012.

Explaining the difference

Why does the Kurdish government appear more committed to gender mainstreaming than the Iraqi government? Why do women in Iraqi Kurdistan feel relatively better off compared to women in the rest of Iraq?

Iraqi Kurdistan and the rest of Iraq have historically shared more or less similar cultural values regarding women’s position in the society. This is not to say that Iraq is a homogenous society when it comes to views on women, but differences in the outcomes towards women cannot be explained by reference to Kurdish versus Arab values (Al-Ali). Moreover, women activists in Iraqi Kurdistan and the rest of Iraq focus on similar issues, and these groups have played a comparable role in both Iraqi Kurdistan and Iraq.

Therefore, explanations deriving purely from the domestic context cannot fully explain the difference between Iraqi Kurdistan and the rest of Iraq. Similar to previous findings by Voller, my research has found that Iraqi Kurdistan adopts better practices when it comes to gender equality in order to increase its credibility in the international arena and thereby bolster its bid to attain recognised independent status. Adopting and implementing universal women’s rights is part of this strategy. Another, perhaps even more fundamental factor is that the majority of Kurdish society and Kurdish political elites perceive international involvement in Kurdish domestic affairs as something positive.

This positive perception is caused by two underlying factors: the deep integration of the international actors into Kurdish domestic affairs, and the benefits of international involvement for the Kurdish nationalist aspirations for statehood. Although many scholars rightly argue there are downsides to international involvement, interestingly the level of criticism towards international actors is relatively low in Iraqi Kurdistan compared to the rest of Iraq.

Recent international involvement in Iraqi Kurdistan goes back to 1991 (earlier involvement dates back to the British mandate rule until 1932), when the US intervened to create a no-fly zone over the Kurdish-populated region of northern Iraq and simultaneously transform it into a de facto autonomous region. Foreign support has also had positive economic and infrastructural impacts. UN agencies, international NGOs and foreign states have served as providers of relief support in the post-Gulf War period, they have undertaken infrastructure building, and delivered the UN Oil-for-Food Programme.

Such international involvement created a context in which the local population, government offices, and ministries all work closely with international actors, including UN agencies, foreign state departments and UN assistance missions. International actors take this opportunity to encourage ideas and values around gender equality and empowerment, and the prevention of gender discrimination in domestic law. For instance, the Kurdish government has been working in collaboration with the UN Assistance Mission in Iraq to reform the legal system and political institutions in accordance with the UN’s values towards human rights, democracy and gender. Indeed, international support has been instrumental in building the economic, social, political, developmental and educational capacity in Iraqi Kurdistan.

Iraqi Kurdistan perceives this level of international involvement positively because it benefits Kurdish nationalist aspirations for statehood. Kurdish independence has had a symbiotic relationship with international intervention. The interventions in 1991 and 2003 facilitated the gradual increase in Kurdish self-rule in Iraq. Moreover, the Kurdish government needs political, financial and military support to bolster its legitimacy and power. Although international involvement and aid has further increased Iraqi Kurdistan’s dependence on external actors (Natali) and has been conditional on the region remaining part of Iraq, it has also further boosted their independence from the Iraqi government in Baghdad.

The cumulative effect is that long-term international involvement in the Kurdish region of Iraq has led to three consequences: (1) increased sovereign rule in Kurdistan vis-à-vis Baghdad; (2) the integration of international actors into the domestic administrative, political, economic and social life Iraqi Kurdistan; and (3) the perception that closer connections to the outside world is a way for Iraqi Kurdistan to achieve its long-term goal of independence. Due to the conditionality of international aid and the need for international support to achieve national interests, Iraqi Kurdistan is heavily incentivised to adopt international gender norms in a way that the rest of Iraq was not.

This does not mean that Iraqi Kurdistan does relatively well on women’s rights simply and purely for these reasons. There’s a long history of women’s rights activism in Iraq and in Iraqi Kurdistan. Momentum from below to enact change alongside a willingness to realise this change among certain sections of policy-makers has undoubtedly been vital too. However, the long-term integration of international actors into the political-economic structure of the Kurdish society and Iraqi Kurdistan’s aspiration for statehood have led to Kurdistan being a better place to live as a woman compared to Iraq.

This article is published in association with the Westminster Foundation for Democracy, which is seeking to contribute to public knowledge about effective democracy-strengthening by leading a discussion on openDemocracy about what approaches work best. Views expressed herein do not necessarily reflect those of WFD. WFD’s programmes bring together parliamentary and political party expertise to help developing countries and countries transitioning to democracy.

Comments

We encourage anyone to comment, please consult the oD commenting guidelines if you have any questions.