|

|

February 27, 2005

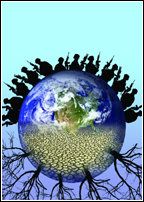

Water disputes

Water management is crucial to peace initiatives around the globe, write Aaron T. Wolf, Annika Kramer, Alexander Carius and Geoffrey D. Dabelko

Water management is crucial to peace initiatives around the globe, write Aaron T. Wolf, Annika Kramer, Alexander Carius and Geoffrey D. Dabelko

INTERNAL water conflicts have led to fighting between downstream and upstream users along the Cauvery River in India and between Native Americans and European settlers. In 1934, the landlocked state of Arizona commissioned a navy (it consisted of one ferryboat) and sent its state militia to stop a dam and diversion project on the Colorado River. Water-related disputes can also engender civil disobedience, acts of sabotage, and violent protest. In the Chinese province of Shandong, thousands of farmers clashed with police in July of 2000 because the government planned to divert agricultural irrigation water to cities and industries. Several people died in the riots

National instability can also be provoked by poor or inequitable water services management. Disputes arise over system connections for suburban or rural areas, service liability, and especially prices. In most countries, the state is responsible for providing drinking water; even if concessions are transferred to private companies, the state usually remains responsible for service. Disputes over water supply management therefore usually arise between communities and state authorities.

Protests are particularly likely when the public suspects that water services are managed in a corrupt manner or that public resources are diverted for private gain.

Local impacts

As water quality degrades or quantity diminishes, it can affect people’s health and destroy livelihoods that depend on water. Agriculture uses two thirds of the world’s water and is the greatest source of livelihoods, especially in developing countries, where a large portion of the population depends on subsistence farming. Sandra Postel’s list of countries that rely heavily on declining water supplies for irrigation includes eight that currently concern the security community: Bangladesh, China, Egypt, India, Iran, Iraq, Pakistan, and Uzbekistan. When access to irrigation water is cut off, groups of unemployed, disgruntled men may be forced out of the countryside and into the city — an established contributor to political instability. Migration can cause tensions between communities, especially when it increases pressure on already scarce resources, and cross-boundary migration can contribute to interstate tensions.

Thus, water problems can contribute to local instability, which in turn can destabilize a nation or an entire region. In this indirect way, water contributes to international and national disputes, even though the parties are not fighting explicitly about water. During the 30 years that Israel occupied the Gaza Strip, for example, water quality deteriorated steadily, saltwater intruded into local wells and water-related diseases took a toll on the residents. In 1987, the second intifada began in the Gaza Strip, and the uprising quickly spread throughout the West Bank. While it would be simplistic to claim that deteriorating water quality caused the violence, it undoubtedly exacerbated an already tenuous situation by damaging health and livelihoods.

An examination of relations between India and Bangladesh demonstrates that local instabilities can spring from international water disputes and exacerbate international tensions. In the 1960s, India built a dam at Farakka, diverting a portion of the Ganges from Bangladesh to flush silt from Calcutta’s seaport, some 100 miles to the south. In Bangladesh, the reduced flow depleted surface water and ground water, impeded navigation, increased salinity, degraded fisheries, and endangered water supplies and public health, leading some Bangladeshis to migrate — many, ironically, to India.

So, while no “water wars” have occurred, the lack of clean fresh water or the competition over access to water resources has occasionally led to intense political instability that resulted in acute violence, albeit on a small scale. Insufficient access to water is a major cause of lost livelihoods and thus fuels livelihood-related conflicts. Environmental protection, peace, and stability are unlikely to be realized in a world in which so many suffer from poverty.

Institutional capacity

Many analysts who write about water politics, especially those who explicitly address the issue of water conflicts, assume that scarcity of such a critical resource drives people to conflict. It seems intuitive: the less water there is, the more dearly it is held and the more likely it is that people will fight over it. Recent research on indicators for transboundary water conflict, however, did not find any statistically significant physical parameters — arid climates were no more conflict-prone than humid ones, and international cooperation actually increased during droughts. In fact, no single variable proved causal: democracies were as susceptible to conflict as autocracies, rich countries as poor ones, densely populated countries as sparsely populated ones, and large countries as small ones.

When Oregon State University researchers looked closely at water management practices in arid countries, they found institutional capacity was the key to success. Naturally arid countries cooperate on water: to live in a water-scarce environment, people develop institutional strategies — formal treaties, informal working groups, or generally warm relations — for adapting to it. The researchers also found that the likelihood of conflict increases significantly if two factors come into play. First, conflict is more likely if the basin’s physical or political setting undergoes a large or rapid change, such as the construction of a dam, an irrigation scheme, or territorial realignment. Second, conflict is more likely if existing institutions are unable to absorb and effectively manage that change.

Water resource management institutions have to be strong to balance competing interests and to manage water scarcity (which is often the result of previous mismanagement), and they can even become a matter of dispute themselves. In international river basins, water management institutions typically fail to manage conflicts when there is no treaty spelling out each nation’s rights and responsibilities nor any implicit agreements or cooperative arrangements.

Similarly, at the national and local level it is not the lack of water that leads to conflict but the way it is governed and managed. Many countries need stronger policies to regulate water use and enable equitable and sustainable management. Especially in developing countries, water management institutions often lack the human, technical and financial resources to develop comprehensive management plans and ensure their implementation.

Moreover, in many countries decision-making authority is spread among different institutions responsible for agriculture, fisheries, water supply, regional development, tourism, transport, or conservation and environment, so that different management approaches serve contradictory objectives. Formal and customary management practices can also be contradictory, as demonstrated in Cochabamba, where formal provisions of the 1999 Bolivian Water Services Law conflicted with customary groundwater use by farmers’ associations.

In countries without a formal system of water use permits or adequate enforcement and monitoring, more powerful water users can override the customary rights of local communities. If institutions allocate water inequitably between social groups, the risk of public protest and conflict increases. In South Africa, the apartheid regime allocated water to favour the white minority. This “ecological marginalization” heightened the black population’s grievances and contributed to social instability, which ultimately led to the end of the regime.

Institutions can also distribute costs and benefits unequally: revenues from major water infrastructure projects, such as large dams or irrigation schemes, usually benefit only a small elite, leaving local communities to cope with the resulting environmental and social impacts, often with little compensation.

The various parties to water conflicts often have differing perceptions of legal rights, the technical nature of the problem, the cost of solving it, and the allocation of costs among stakeholders. Reliable sources of information acceptable to all stakeholders are therefore essential for any joint efforts. This not only enables water-sharing parties to make decisions based on a shared understanding, it also helps build trust.

A reliable database, including meteorological, hydrological, and socioeconomic data, is a fundamental tool for deliberate and farsighted water management. Hydrological and meteorological data collected upstream are crucial for decision-making downstream. And in emergencies such as floods, this information is required to protect human and environmental health. Tensions between different water users can emerge when information is not exchanged. Disparities in stakeholders’ capacity to generate, interpret, and legitimize data can lead to mistrust of those with better information and support system. In the Incomati and Maputo River basins, the South African monopoly over data generation created such discomfort in downstream Mozambique that the basins’ Piggs Peak Agreement broke down, and Mozambique used this negotiation impasse to start enveloping its own data.

The crux of water disputes is still about little more than opening a diversion gate or garbage floating downstream.

Cooperative water management is a challenging issue that requires time and commitment. Extensive stakeholder participation might not always be feasible; in some cases, it may not even be advisable. On any scale of water management, if the level of dispute is too high and the disparities are too great, conflicting parties are not likely to reach consensus and might even refuse to participate in cooperative management activities. In such cases, confidence and consensus-building measures, such as joint training or joint fact-finding, will support cooperative decision-making.

Conflict transformation measures involving a neutral third party, such as mediation, facilitation, or arbitration, are helpful in cases with open disputes over water resources management. Related parties, such as elders, women, or water experts, have successfully initiated cooperation where the conflicting groups could not meet. The women-led Wajir Peace Initiative, for example, helped reduce violent conflict between pastoralists in Kenya, where access to water was one issue in the conflict. In certain highly contentious cases, such as the Nile Basin, an “elite model” that seeks consensus between high-level representatives before encouraging broader participation has enjoyed some success in developing a shared vision for basin management. Effectively integrating public participation is now the key challenge for long-term implementation of elite-negotiated efforts.

Water management is, by definition, conflict management. For all the 21st century wizardry-dynamic modeling, remote sensing, geographic information systems, desalination, biotechnology, or demand management — and the new-found concern with globalization and privatization — the crux of water disputes is still about little more than opening a diversion gate or garbage floating downstream. Yet anyone attempting to manage water-related conflicts must keep in mind that rather than being simply another environmental input, water is regularly treated as a security issue, a gift of nature, or a focal point for local society. Disputes, therefore, are more than “simply” fights over a quantity of a resource; they are arguments over conflicting attitudes, meanings, and contexts.

Obviously, there are no guarantees that the future will look like the past; the worlds of water and conflict are undergoing slow but steady changes. An unprecedented number of people lack access to a safe, stable supply of water. As exploitation of the world’s water supplies increases, quality is becoming a more serious problem than quantity, and water use is shifting to less traditional sources like deep fossil aquifers, wastewater reclamation, and inter-basin transfers. Conflict, too, is becoming less traditional, driven increasingly by internal or local pressures or, more subtly, by poverty and instability. These changes suggest that tomorrow’s water disputes may look very different from today’s.

On the other hand, water is a productive pathway for confidence building, cooperation, and arguably conflict prevention, even in particularly contentious basins. In some cases, water offers one of the few paths for dialogue to navigate an otherwise heated bilateral conflict. In politically unsettled regions, water is often essential to regional development negotiations that serve as de facto conflict-prevention strategies. Environmental cooperation — especially cooperation in water resources management — has been identified as a potential catalyst for peacemaking.

So far, attempts to translate the findings from the environment and conflict debate into a positive, practical policy framework for environmental cooperation and sustainable peace show some signs of promise but have not been widely discussed or practised. More research could elucidate how water — being international, indispensable, and emotional — can serve as a cornerstone for confidence building and a potential entry point for peace. Once the conditions determining whether water contributes to conflict or to cooperation are better understood, mutually beneficial integration and cooperation around water resources could be used more effectively to head off conflict and to support sustainable peace among states and groups within societies.

Excerpted with permission from

State of the World 2005: Redefining Global Security

Edited by Linda Starke

Worldwatch Institute, www.worldwatch.org

W.W. Norton & Company, Inc. 500 Fifth Avenue,

New York, N.Y. 10110

ISBN 0-393-06020-9237pp. $18.95

|

|