Zimbabwe’s electoral observers hold the line in Harare – Julia Gallagher in Harare

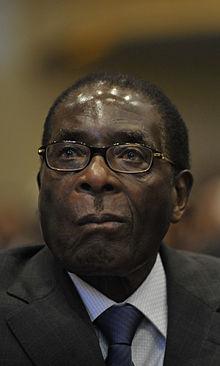

Zimbabwe’s harmonised election – to decide local, parliamentary and presidential seats – has been surprisingly relaxed so far, with calls for non-violence, relatively mild critical exchanges between the candidates and occasional snippets of humour. The ruling ZANU-PF campaign has focused on the opposition’s lack of statesmanship (one election broadcast showed clips of MDC-T leader Morgan Tsvangirai and his colleagues making comments with presumably rude words bleeped out), and its links to the West, contrasted with Robert Mugabe’s efforts to complete the final phase of the revolutionary struggle. Tsvangirai has suggested that Mugabe is old and needs a rest.

In Monday’s Daily News, ZANU-PF took out a full-page advertisement with a photograph of Tsvangirai, Finance Minister Tendai Biti and other MDC-T officials reading a copy of the ZANU-PF manifesto. The caption ran: “˜Our manifesto has excited everyone!’ The following day, the MDC-T came right back at them, showing the same picture but with speech bubbles. Biti says: “˜ZANU yazopererwa manje (ZANU is finished now)’ while Tsvangirai replies: “˜Haiwawo! Musapedzere nguva nenyaya dzanezuro! (Don’t waste your time with these old lies!)’.

But despite the apparent calm, this election is confused and disjointed. In particular, flows of information and misinformation create many different narratives that are taken up and presented by different constituencies to suit their tastes or purposes.

Did people walk out on Robert Mugabe during his two-and-a-half hour speech at Chinhoyi on Wednesday, prompting party officials to beg them to stay and ‘not embarrass the president’? Did Morgan Tsvangirai turn up to an empty venue when he tried to campaign in ZANU-stronghold Mashonaland Central?

Who is calling for a postponement of the election date – is it the opposition which initially argued that the country wasn’t ready, or is it the ruling party which now feels less certain that it can win?

Were the soldiers and police who were involved in special early voting forced to vote in front of their commanding officers, on numbered ballot papers that could be checked afterwards; and, despite this, is it true that leaked results are suggesting a massive vote in favour of the opposition?

Was a new TV station set up to broadcast from Johannesburg a success (people I spoke to claimed it would at last provide Zimbabweans with an unbiased source of broadcast news), or did it fail to launch (as the government-controlled Herald newspaper maintained)?

And underneath the confusion is anxiety. The presidential election is the one that really matters: the constitution adopted earlier this year made several important changes, including provisions for key human rights, but did not address the president’s substantial powers. Mugabe went into the election reasonably confident that he could win. Tsvangirai’s romantic adventures after the death of his wife, his party’s implication in the shaky power-sharing government since 2008, his often demonstrated lack of political judgment, and stories of MDC-T ministers’ incompetence and corruption have harmed him. Meanwhile, the economic situation has improved slightly. Unemployment is still high (an estimated 85 per cent), but the US dollar, used since hyper-inflation led to the collapse of the Zimbabwe dollar, has brought a measure of stability and people are no longer in the state of crisis they were in 2008. It feels as though the country is able to breath again, albeit very slowly and carefully.

Many feel that Tsvangirai has been complacent, assuming that he can continue to capitalise on disaffection rather than prove himself as a president. He has not done a great job of building relationships in power, and his party looks weak and badly organised alongside the still formidable capacity of ZANU-PF. Mugabe, old and frail, is still relatively presidential, and he continues to draw on reserves of respect and affection, particularly in parts of the country that have seen substantial land redistribution. Polls put Tsvangirai and Mugabe neck and neck, on around 45 per cent each, a result that would demand a run-off.

But there are far more significant obstacles in the way of an MDC-T victory; in particular, the potential for electoral fraud, and the intimidation of voters. The organisation of the election, administered by the new Zimbabwe Electoral Commission (ZEC), got off to a shaky start. ZEC has been under-resourced and asked to deliver an election in an eye-wateringly short timeframe (it was some five weeks from the announcement of the date). The registration of voters was shambolic, with long queues and lengthy, bureaucratic procedures which resulted in many potential voters being turned away. Some opposition activists claim that up to 60 per cent of the electorate has been disenfranchised in the process.

The suspicion is that it the worst excesses occurred in opposition strongholds, and many now believe that the ZEC is a ZANU-PF stooge. ZEC now has to provide the ballot papers, boxes and staff to set up polling stations across the country and to run a free and fair election. Even with the cleanest of intentions this is a tall order.

The second obstacle is the fear still felt by large numbers of the electorate. These elections have been virtually free from violence so far, and there is an air of calm and hopeful expectation. But underneath people are frightened. An estimated 200 people were killed in 2008, and thousands fled the country in the violence against MDC-T activists. “˜Elections in Zimbabwe are trauma,’ one Mbare resident told me. “˜People are dreading a run-off particularly. That’s when people lost hands, and really suffered in 2008.’ MDC-T activists I visited in Chitungwiza, a high-density area outside Harare, have installed metal gates and bars on their doors and houses in preparation.

Much of the discussion amongst opposition activists has been around how to persuade people that they should vote with confidence in the secrecy of the ballot box. “˜We say, no one will know what you vote. But then people also know that whole areas were targeted last time because they returned MDC-T candidates.’

A key theme has been how to establish a sense of containment to somehow manage these elections, and to mitigate the confusion, the suspected fraud and the potential violence. I attended a training day for Zimbabwean election observers organised by ZESN – the Zimbabwe Election Support Network. This collection of church, trade union and civil society organisations is trying to get more than 7,000 observers trained in time to staff every polling station in the country. These are people nominated by their organisations, drawn from across the country.

The observers attend a one-day training session in batches of 40 in which they are taught the basics of the new constitution and electoral laws. They are told how the polling stations are laid out – how far the policeman should stand outside the door, how many election officials should be there, what equipment each should have, from ballot-papers to indelible ink and the official stamp, what time the polling station should open and close, who can help voters who need assistance and in what ways, what constitutes a spoiled ballot paper, and where the results are to be posted once the count is finished. They are given forms to fill in details about the number of electors who are turned away, counts of ballot papers used; and ‘serious incident forms’ to file in case they witness transgressions of the process. They are given careful instructions on their personal safety (‘we want living heroes, not dead heroes,’ says the instructor), on how to deal with SADC observers (polite, but not too friendly), and what to do if things aren’t quite right (‘it is your job to point out problems, leave the arguing to the party monitors’).

These people – ordinary citizens – are there to ensure the process runs according to the rules and principles of their new constitution, ‘and we know this will be difficult, because this is Africa, this is Zimbabwe’. They are up against a ruling party that will try everything it can to win this election, and they are there to try and keep it free and fair, and to record the voting process so that ZESN can produce an authoritative account afterwards.

At the end of the day they stand, raise their right hands, and together read out the election observers’ charter. They will not display party symbols or campaign for any party; they will not interfere in the election process; they will commit themselves to the constitution and the authority of the ZEC.

These people are going to try to provide both a narrative of this election, and a measure of coherence and stability that no one else is prepared or able to. They do look rather small and fragile going into this – and it is difficult to see that there will be enough of them in the short timescale given – but in the absence of any other sense of containment, they are going to try and hold the line.

Julia Gallagher is a lecturer in international relations at Royal Holloway, University of London.