‘The Intelligent Hand’ at the Fab Lab

Professor Trevor Marchand writes…

On the evening of Tuesday March 15, I screened my new documentary film, The Intelligent Hand, at the Fab Lab in the City of London. The event was hosted by the RSA Inequality in Education Network and attracted a diverse audience of educators, university academics, practicing craftspeople, woodwork trainees, and professionals from various sectors.

See The Intelligent Hand here…

I introduced the film with a short talk on craftwork and education, and the screening was followed by a period of focussed discussion amongst audience members in small groupings. In turn, this set the scene for an open Q&A and general conversation. Our discussion was framed by the broad question: ‘What needs to change in order to make vocational education and craftwork attractive options in Britain?’

This article provides a synopsis of my introductory talk before offering a summary of the key issues raised by audience members in conversation.

Introductory Talk

I began my talk with a brief overview of the anthropological fieldwork I have carried out over the past two decades with minaret builders in Yemen, mud-brick masons in Mali, and fine woodwork trainees in Britain. Each of these studies aimed to understand the technical, social and cultural mechanics of apprenticeship systems and skill-based learning. My research has been part of a burgeoning interest among social scientists, educators, and cognitive and neuroscientists in embodied ways of learning and knowing. My ethnographic approach has endeavoured to move the study of human knowledge well beyond what people say and think to include what they actually do, in practice.

My findings robustly challenge the enduring Cartesian division made between internal mind operations and physical doing. The data demonstrates that craftspeople are thinking with tools-in-hand, and they are actively engaged with materials, other actors, and the surrounding environment in their pursuits to solve problems, enhance skills, broaden knowledge, and construct social identities and professional status.

Calculating, theorising, setting goals, imagining outcomes, and working out hypothetical pathways toward a solution are very much a part of both design and making in craftwork. But, equally, physicists, mathematicians, and philosophers engage bodily and sensorily with the world in solving the tasks and problems they set for themselves. In sum, my introductory talk demonstrated that the boundary drawn between ‘academic’ and ‘hands-on’ work is less tidy and far more porous than what is popularly assumed.

To conclude, I stressed that practical skill learning is not ‘unthinking imitation’. Rather, it involves multiple and highly complex forms (of often non-verbal) communication and, like scholarly knowledge, skilled practice is a hard-earned cognitive achievement. Britain’s education policies therefore need to be reformed around a more holistic definition of ‘knowledge’ – one that recognises the unity of mind and body and that desists from imputing hierarchy between them.

Practical know-how must be accorded the value and status that it merits: not merely for increasing economic productivity or reducing the nation’s skills gap, but more importantly craftwork should be celebrated and promoted as an attractive career path leading to satisfying work and life.

Audience Discussion

‘What needs to change in order to make vocational education and craftwork attractive options in Britain?’ This question generated our open conversation. Audience members broke into discussion groups and an individual from each volunteered to act as spokesperson, offering a summary of the key ideas, issues, and further questions that arose. A general conversation followed.

Angela launched the exchange with her group’s observation that, historically, England’s education policy has been framed by a persistent mind-body dualism. By contrast, she urged recognition of ‘the parity between using one’s brain and one’s hands’, and she drew our attention to the Steiner School example and its emphasis on learning-by-doing. Anna later noted that tuition fees for Steiner Schools were prohibitively costly for the average family, while, distressingly, state school curricula for young children includes little if any practical hands-on learning.

Cheryl, a college woodworking instructor in the audience, added that, regrettably, ‘many secondary schools no longer host woodworking courses: it’s expensive; it takes up a lot of space; the tools and machinery are expensive; and the overheads are expensive.’ As a consequence, career options in the crafts and trades are made invisible to British youth. As one audience member said, ‘there is a need to make craftspeople role models’. Like sports celebrities, artists, and renowned chefs, their names, skills, values, and contributions to society need to be made part of popular public discourse.

Both David and Sam, as spokesmen for their groups, interrogated the entrenched divide between academic and vocational education, and society’s tendency to stereotype ‘vocational education’ as ‘a cheap job-training scheme, providing a basic level of skills to get people into employment’. The ambiguity of the term ‘vocational’ and its relation to the equally woolly category ‘craft’ was raised.

Emma, a furniture maker, queried the distinction made at her college between fine woodwork as a craft and the bench joinery programme as a vocational route. It was suggested that the NVQ framework has had the effect of narrowing popular understanding of ‘vocational’ as a kind of ‘non-academic, technical training’ for tradespeople, craftspeople, and technicians. In the past, by contrast, vocational training also encompassed the education of lawyers, architects, engineers, and medical doctors. Training in these latter disciplines became firmly established within the university; and today, Sam noted, university qualifications are ‘perceived as more valuable’ and therefore ‘fetch greater remuneration in the job market’.

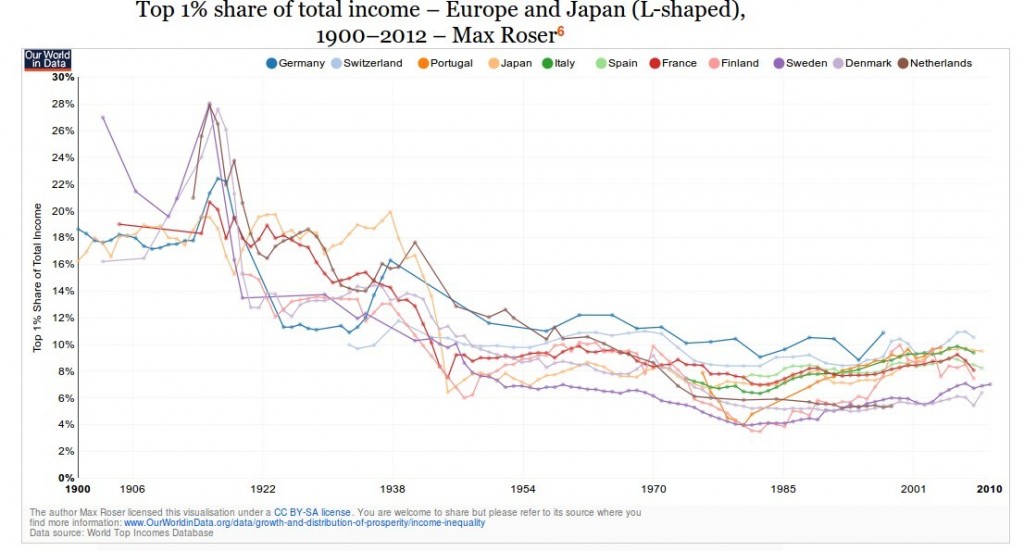

One participant in Wendy’s group was Swiss, and another Swedish, and together they discussed ‘the differences between Britain and other countries’ in terms of the structural relations between academic and vocational/craft pathways. It emerged that in some European countries it is easier to ‘cross from one to the other’, depending on what kinds of skills and knowledge an individual needs at different points in their professional development.

In Enna’s group, one university student described the Institute of Making at UCL, which, according to its website, is ‘a cross-disciplinary research club for those interested in the made world,’ from molecules to buildings. Group members extolled the notion that ‘doing something with your hands should not be divorced from a university education’.

Joe, as spokesman for his group, asked ‘Can computer coding be considered a craft?’ In response, I recounted my arrival at the Fab Lab earlier that evening, when a young man working there inquired about the subject of my talk. I replied, ‘The importance of craftwork’. He smiled, saying, ‘Oh great! I can relate to that.’ I asked what he did. He told me, ‘I design circuit boards’. In our brief exchange, he made no hesitation in relating his work to ‘craft’: circuit board design, like blowing glass or potting, involves a unity of hands and mind in making, experimenting, and creatively solving problems as they arise.

Another audience member added that he too viewed his work as a craft. He claimed that as a management consultant who analyses and solves business problems, his practice ‘combines art and science’. ‘It involves whole-body learning,’ he continued. ‘It’s about perception, it’s about understanding situations and being able to interpret them. I just use a different set of tools from planes and chisels.’

The subject of ‘power and inequality’ was also tabled for discussion. Graham proclaimed that, ultimately, ‘it’s all about power: about empowering people to bring about social and economic change’. He lamented craft’s second-class status and ventured, ‘If people – in education, in politics, in society – could be made to understand that craftwork can be powerful, it would move mountains. But until we achieve that realisation, we’ll carry on with the malaise that we’ve got.’ Richard highlighted the perverse fact that those most handsomely remunerated are those in the finance sector ‘who make absolutely nothing: they don’t make things, they don’t make books, they don’t make education, they don’t heal us of our ills.’

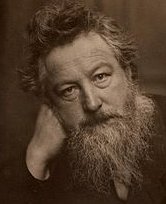

In thinking about ‘what needs to change’, Catherine pointed to the kinds of social reform advocated by William Morris, and argued for the continued relevance of his ideas. According to Rachel, the starting point for change needs to be with us, the consumers: ‘We need to stop buying cheap sh** from IKEA. We need to seriously understand the value of an object and the effort that goes into making something.’ Emma, the furniture maker, shared her story of struggle to make a living as a craftsperson and the need to find work outside her practice in order to make a living and survive. Wendy, too, told us of friends who tried to set up as woodworkers, and failed. ‘Alongside craft skills need to go business skills,’ she said, and that needs to be a core part of craft and any other kind of vocational training.

Brian underscored the need to focus on inequality, as it is made manifest in power structures, gender hierarchies, social-class privilege and, importantly, access to education, training and work within the craft sector. He felt that craft has an important role to play in counteracting inequality in its various guises. In the UK, for example, women and minority groups are patently underrepresented in carpentry, and niche practices such as fine woodwork and furniture-making are dominated by trainees and practitioners from the middle classes.

Concerning gender, Cheryl, the college instructor, noted that in some years no female trainees enrol on the fine-woodwork programme. She could not explain why this happens, especially since ‘there is not the same stigma attached to going into the carpentry trades for girls as there is for boys’. It is often perceived that boys going into the trades must have failed or performed poorly in school. Cheryl recounted her own experience:

‘I went to an all-girls’ grammar school, and my parents were both teachers. So I can’t image that if I were a guy I would have ended up an apprentice on a Southwark council scheme. But that was a wise move for me: I received wages to go to college and get an education, and the qualifications to eventually become a teacher and an assessor. I don’t think that could have happened if I were a boy.’

Charlotte offered some final thoughts on the original question I had posed. She invested hope in the emerging neuroscience discourse to positively change popular (mis)conceptions about the mind-body relation.

‘The neurosciences are informing us that learning is a whole-body activity: that it involves posture and rhythm; it’s about connection to tools; and it involves training vision and touch. All forms of education and work demand that our sensory capabilities are fully developed. When an individual is developed in this way, they are both craftsperson and academic, endowed with creative understanding. We need to develop people broadly.’

Thanks

Thanks to the Inequality in Education Network, and especially John Bayley and Lynda Haddock for organising and mediating the event. Thanks to Fab Lab for graciously hosting us. And thanks to all those who attended and participated in what was – I hope for all – an evening of stimulating conversation and exchange.

Review by Prof. Trevor Marchand.

You can see the full creative credits for The Intelligent Hand on our films page here…(Ed.)